by Jakiat Jitu

Introduction

Bangladesh is the seventh most vulnerable country to climate change according to the The Global Climate Risk Index (2021) due to its unique topography and location, paired with the inability of society and institutions to cope with extreme events (Eckstein, Kunzel and Schafer, 2021). The country faces fatalistic devastation by various natural hazards due to inadequate infrastructure and disaster-resilient framework. Despite these challenges, 29% of the population continues to live in coastal areas, coping with the dangers of changing environments by utilizing indigenous practices (Kamal Uddin and Kaudstaal, 2003).

Understanding the existing scale and nature of indigenous coping strategies is important to build resilience at the household and community levels to develop adaptation plans (Huq and Reid, 2007). Excerpting from the National and local level actions from the Sendai Framework, the Bangladesh government has enlisted the incorporation of indigenous knowledge and practises into the National Plan for Disaster Management (2021-2025) (Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief, 2020). Although some NGOs are working to integrate indigenous coping strategies for awareness, practically implementing this policy is still absent due to limited resources (Partha, 2024; Ullah, 2024).

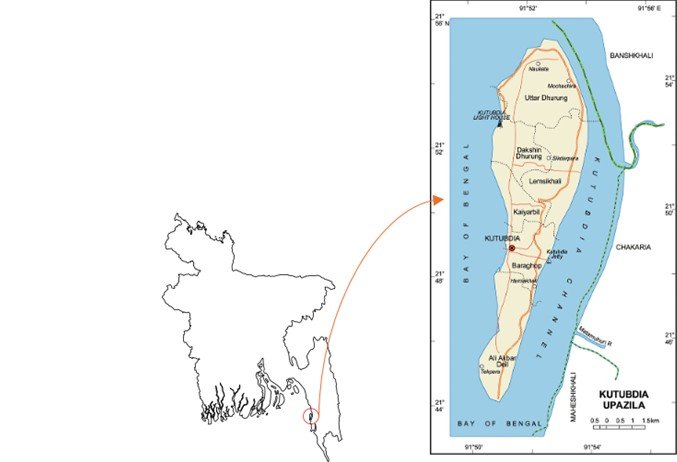

Highlighting Kutubdia of Bangladesh, this essay aims to understand the role of indigenous knowledge as built environment resilience at a homestead scale within the context of disaster risk reduction (DRR). What disasters occur in Kutubdia, and how do they affect the built environment? How do Kutubdia residents use indigenous knowledge to cope with disaster risk?

This essay first elaborates on the general profile of Kutubdia and its infrastructure. Next, specific disasters that affect Kutubdia’s built environment are analysed, followed by an exploration of specific indigenous coping strategies focused on physical strategies through analyses of relevant literature and field observations. Finally, this essay evaluates the constraints of these indigenous practices.

Profile of Kutubdia

The small island of Kutubdia , situated on Bangladesh's southeastern coast, is disconnected from the mainland by the Kutubdia Channel. The landscape is composed of captivating sandy shores, numerous salt beds and lush mangrove forest. The 10-acre mangrove forest created in 1986 has been slowly shrinking since 1990 due to growth of shrimp enclosures and salt fields, hampering the ecological barrier and increasing vulnerability to disasters (Kuddus, 2024).

Despite being upgraded to a sub-district in 1983, Kutubdia as of 2024 still lacks infrastructure and administrative care as compared to mainland sub-districts. The island hosts several primary and secondary schools, a few healthcare facilities and multiple cyclone shelters. Most public buildings in Kutubdia are designed as multipurpose centres that act as shelters during disasters.

Although a network of internal roads is present on the island, they are frequently damaged by flooding and erosion. A 40 km embankment in disrepair surrounds the island and is susceptible to erosion. Recently, more than 18 km have been partially repaired by the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) (Billah, 2022). The island has limited access to electricity from the largest wind power station but also relies on solar power (Adaan Uzzaman, 2023). Tube wells and rainwater harvesting serve as the primary water supply.

Most Kutubdia residents are salt farmers earning up to only £650 annually without the oversight of any formal rules and regulations (Bangladesh National Social Welfare Council, 2022). Consequently, they suffer from severe health conditions and workplace exploitations. Other residents work as farmers, fishermen and rikshaw pullers. Salt farming, being a seasonal occasion, leads salt farmers to work in fishing, livestock rearing, or as day labourers during unemployment. The opportunities for formal employment are inadequate.

Disaster Hazards in Kutubdia

Kutubdia is particularly vulnerable to natural hazards, especially cyclones, storm surges, floods and coastal eruptions. Environmental degradation and climate change are intensifying the frequency and impact of these natural hazards, transforming historically occurring natural hazards into compound crises (Barua, Rahman and Fellow, 2017). For centuries, the fisherman and farmer communities of Kutubdia have been coping with natural hazards, but recently climate change and pollution have been intensifying their vulnerabilities.

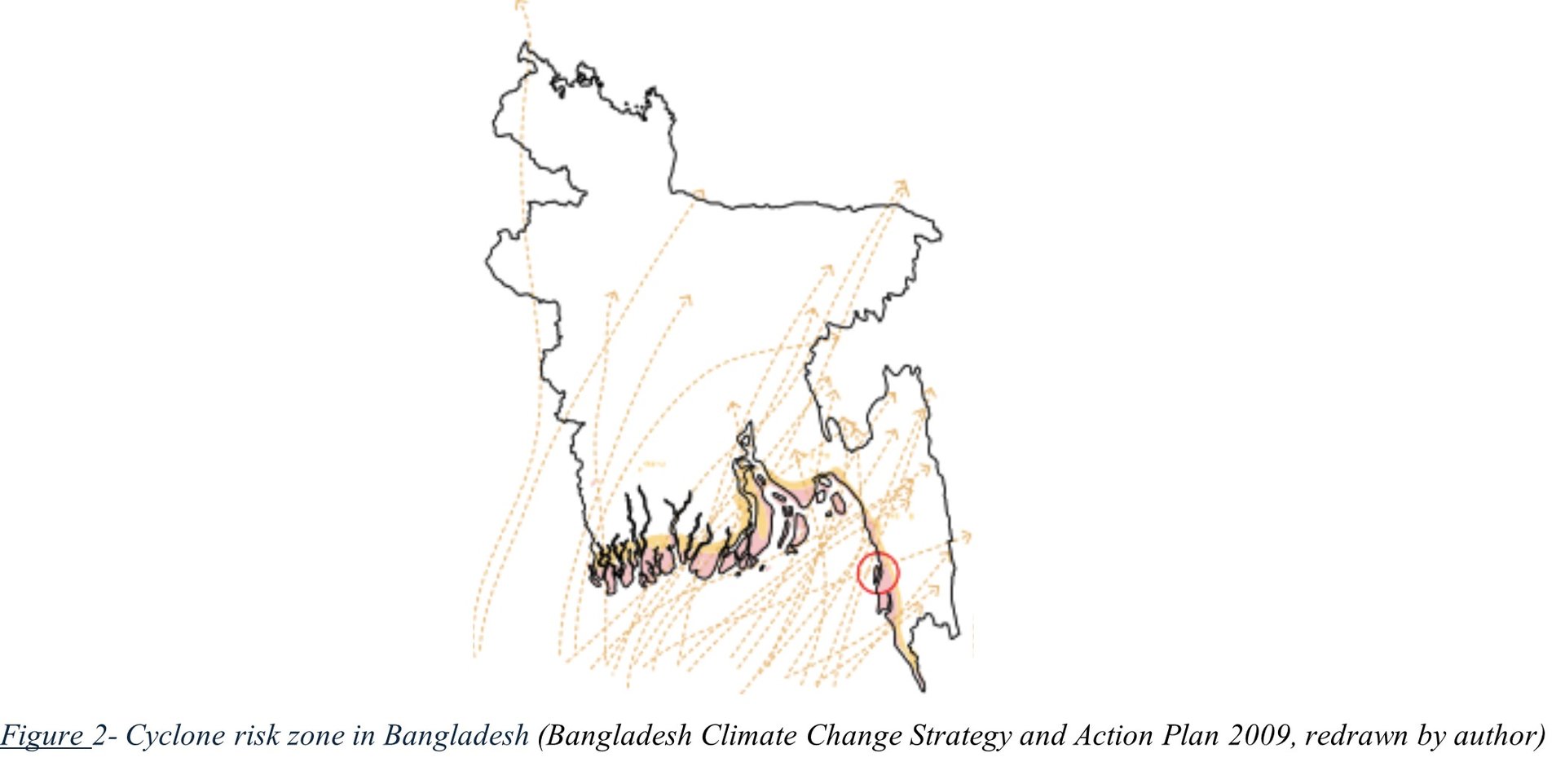

Cyclones

Kutubdia is in the most cyclone-prone zone in Bangladesh (marked in orange). Cyclones typically develop annually in the pre-monsoon (April-May) and post-monsoon (October-November) periods. Each year during cyclone season due to flooding and storm surges the island suffers from extensive infrastructure damage, environmental degradation, economic losses, health risks, displacement, and migration triggered by loss of livelihoods and homes (Hasan and Navera, 2012).

Disastrous cyclones of 1970 and 1991 still haunt the residents of Kutubdia. Almost every Kutubdia resident has a traumatic history of losing family members, homes, land, and memories. With storm surges up to 6 metres and more than 138,000 fatalities combined, these two cyclones led to a call for disaster preparedness and response mechanism improvements coupled with political and social upheaval in the region (MetLink, 2020).

Most recently, Cyclone Hamoon, on October 24, 2023, injured 30 individuals, caused extensive damage to shops, homes and infrastructures and uprooted approximately 10,000 trees. Hamoon led to disruption of communication, power outages, and significant economic losses (Hossain and Islam, 2023).

Flood and Storm Surge

The 1991 cyclone caused the most devastating flood in Kutubdia’s history, destroying 80-90% of all structures. Flood duration varies based on the severity of the storm surge and drainage systems efficiency. In low-lying areas, flood water often remains for extended periods, causing water damage to infrastructure, homes, and crops and increasing waterborne disease risk. High tides also cause flooding, especially during spring tides, river flooding, and intense rainfall over a brief period, causing flash floods. The rapid rise in water levels causes sudden and severe damage to infrastructure and Crops. Recently, tidal surges of July 8, 2019, marooned over 10,000 villagers, inundated up to 16 villages, and damaged homes and agricultural land causing major disruption of daily life (The Financial Express, 2018; The Financial Express, 2019)

Rising Sea Levels

Kutubdia, being 1 metre above mean sea level, is highly vulnerable to rising sea levels. Climate change and global warming are melting polar ice caps contributing to sea-level rise. There is an increasing risk of flooding and coastal erosion, with projections indicating sea level could rise to 77 centimetres by 2100 (NASA, 2021). Rising sea levels also cause saltwater intrusion, affecting plant growth, agriculture and degrading construction materials in coastal areas.

Saltwater Intrusion

Saltwater intrusion is caused by a combination of natural and human-induced factors. Frequent storm surge cyclones and rising sea levels allow salt water to penetrate and contaminate inland freshwater sources, increasing the salinity. Over-extraction of groundwater for drinking purposes and irrigation draws saltwater intrusion into freshwater aquifers. Salt farming is also contributing to the increased salinity of the ground. The intrusion reduces the fertility of soil and crop yields, putting food security, livelihoods and health at risk (Islam et al., 2023). Salinity corrodes vernacular building materials and hinders plant growth and kitchen gardens.

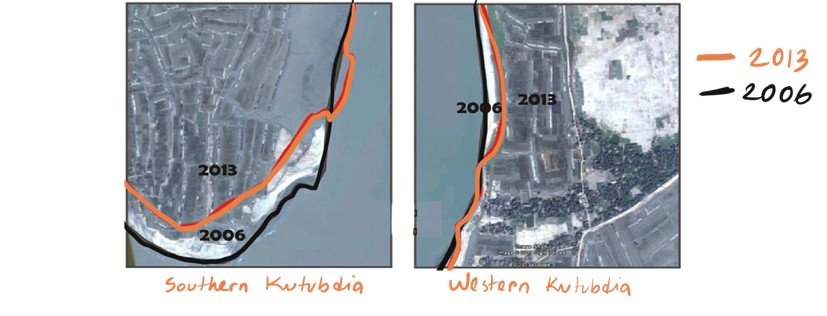

Coastal Erosion

The geographical location makes Kutubdia highly susceptible to strong tidal waves and storm surges, which erode the shoreline, leading to substantial land loss. Sea-level rise is exaggerating coastal erosion with increasing frequency and intensity of tidal inundation. Human activities such as salt mining and mangrove deforestation further reduce the natural barrier of the coastline. Coast Trust, a nonprofit organization, predicts that the island may vanish from the map within 70 years if the current erosion rate continues (Tanim and Roy, 2013). The loss of land has exacerbated economic hardships, displacement and migration (Chowdhury, 2021).

Disaster Effects

The consequences of these compounded hazards are profound. Thousands of people have been displaced from Kutubdia due to disaster hazards leading to the loss of homes, arable land, and livelihoods (Hossain et al., 2020). This has led to a steady migration from Kutubdia to the mainland and other regions, placing pressure on urban areas. The remaining population face extreme poverty due to disrupted fishing and agriculture, which diminishes the community's adaptive capacity and resilience further (Islam et al., 2023).

Coping Strategies

Physical Coping Strategies- Before the Disasters

Most homes are oriented in the east-west direction to minimise wind damage. Traditional houses usually follow the "Pashchati " design, where the balcony surrounds the core rooms (bedroom, storage). Pashchati acts as a barrier against high winds and rain, reducing water penetration. The typical house layout is rectangular, sequentially including a small front yard at the entrance, leading to the common room (also used as a living room), bedrooms, a kitchen, a kitchen garden, and a pond on either side.

Alternatively, some houses follow a square format, with a balcony surrounding the living room and bedrooms, with an extending kitchen connected to the backyard or pond. As the entire island is flood-prone, sandbags or earth bags are used as paving blocks in yards. Drainage systems are typically located at the sides of the homes, connected to the ponds, facilitating the easy passage of floodwater. Many houses also feature elevated dykes, and bamboo revetments, which are seen to mitigate wave impact and prevent coastal erosion (Barua, Rahman and Fellow, 2017).

Hipped roofs are prevalent, combining a Pashchati roof over the balcony and a central roof (Haq and Chattopadhayay-Dutt, 2007). Roof corners are secured with ropes, and bricks, heavy sacks, or sticks (often repurposed as fuel) are placed on top for added stability. Fishing community houses tend to have low plinths, often below 1.5 feet (45.72 cm), allowing floodwater to pass through. Windows are typically small or absent; however, high windows are present for ventilation while minimising wind damage. These windows are often fitted with woven bamboo-jali to ensure privacy.

Unique ergonomic features are observed in some houses, including low-height doors of 4 to 4.5 feet (121.92 to 137.16 cm). Main entrance doors may have a barrier, approximately 1 foot (30.48 cm) high from the ground, preventing ducks and chickens from leaving the homestead. Innovative storage solutions such as kitchen shelves and hooks fashioned from vernacular materials are common.

The choice of construction materials reflects homeowners' financial capacity on this island. Most houses use vernacular materials such as bamboo, wood, cane, and sticks for walls, earthen plinths, and straw roofs. Wealthier residents utilise brick or concrete walls, concrete plinths, and corrugated tin roofs.

The island’s proximity to the Chittagong shipbreaking yard facilitates access to recycled construction materials, forming a distinctive vernacular practice. Reclaimed ship materials, including water-resistant wooden boards, recycled doors, beams, and metal panels, are used at the homestead scale.

Additionally, recycled fishnets and polythene sheets from saltwater farms are widely employed. Polythene sheets are incorporated into roofs and walls, sometimes woven into bamboo frames and tied with rope. Fishing nets are repurposed in diverse ways, such as canopies over courtyards, often supporting climbing vine plants. This reliance on recycled materials not only reduces costs but also promotes waste reduction and environmental sustainability.

Physical Coping Strategies- During the Disasters

During disasters, 46% of residents take refuge in cyclone shelters (Parvin, Takahashi and Shaw, 2008). Domestic animals such as cows and goats would also be brought to the shelters, including valuables that could be carried. To combat food and water scarcity during disasters, dry food is stored in polythene packets along with safe drinking water in a higher position out of water reach. Additionally, plastic containers are hung at higher positions on the walls for food and water storage.

Physical Coping Strategies- After the Disasters

After a disaster, the priority is rebuilding. Usually, during a cyclone, the roof is the first part of the house to be blown away. Residents attempt to retrieve the roof if possible. Most houses made of vernacular materials deteriorate with flooding, saltwater intrusion, and storm surges that accompany typical cyclones. In such cases, island residents often use polythene sheets like puzzle pieces to patch the missing structural parts.

Nonphysical Practices

In Kutubdia, community participation is central to disaster preparedness and recovery. Residents collaboratively repair embankments, cyclone shelters, and other public structures, with young members playing an active role (Shahriar, 2015). Government and NGO programmes further promote collective efforts to address climate challenges and improve livelihoods (Ullah, 2024). Cultural practices enhance resilience through religious gatherings, which offer emotional support and strengthen social bonds during crises. Kutubdia residents also rely on storytelling and collective memories of past disasters sharing survival techniques, fostering preparedness and community cohesion.

Constraints

Financial limitations remain the most significant constraint for Kutubdia residents. Their ability to accumulate capital is further hindered by frequent cyclones and other extreme weather events. As a result, Fixing roofs and walls with polythene sheets costing approximately 1000 taka (£7) is often unaffordable after a disaster.

Since most indigenous coping strategies are based on vernacular materials, the historically practised strategies against seasonal storms are becoming inadequate in addressing the heightened impacts of climate change. The communities are becoming increasingly vulnerable due to the lack of enhancement in indigenous knowledge and coping strategies in response to the changing climate (Parvin and Johnson, 2012). However, the challenges do not diminish the value of indigenous knowledge rather, they underscore the necessity of learning from the lacking and, enhancing with the help of modern technology and information to enable the capacity of indigenous knowledge to cope with adversity and recover from unforeseen disasters (Kulig, Edge and Joyce, 2008).

The island’s disconnection from the mainland limits exposure to external knowledge and innovation with the capacity to improve resilience. Exposure to contemporary strategies comes through NGOs which are minimal and inadequate to enhance indigenous practices (Ullah, 2024). Most government initiatives at the homestead level utilize a top-down approach with minimal or no opinion from the community, far from active participation or coordination with indigenous knowledge (Parvin and Johnson, 2012).

Despite these challenges, Kutubdia residents are eager to advance their age-old indigenous practice to better cope with intensifying disasters. Recent adoption of recycled shipwreck material within homesteads points to an attitude of adaptation. Since indigenous knowledge is deeply rooted in the community and widely accepted, when effectively combined with scientific approaches, may result in significantly improved DRR strategies (Ikeda, Narama and Gyalson, 2016). By integrating indigenous knowledge into national DRR frameworks, governments and institutions may benefit through increased local awareness and coping capacity to disasters (Enock and Makwara, 2013).

Conclusion

Kutubdia’s vulnerability to climate change is evident by devastations of increasing and intensifying cyclones, storm surges, floods, saltwater erosion, sea-level rising and deadly coastal erosion. But indigenous coping strategies manifest the inherent resilience, with practices such as pashchati, east-west orientation of houses, effective function zoning and adjustments to roofs to reduce wind damage; efficient adjustments to ergonomics of components (roof, door) to lessen wind and water damage; and use of recycled materials (marine board, fishing nets, metal sheets) to lessen corrosion by salt-water.

While indigenous coping strategies offer valuable insight for coping with recurring natural hazards, they remain insufficient in the face of intensifying climate change impacts. Financial constraints limit the ability to rebuild and repair after a disaster. Limited exposure to innovation and the absence of indigenous knowledge integration into national frameworks further exacerbate the challenges faced by Kutubdia residents.

However, the desire to adapt and improve indigenous practices offers a potential path to improve DRR when combined with scientific approaches. Effective enhancement of resilience lies in the synergy of indigenous knowledge and contemporary techniques to ensure better equipment for local communities to withstand and recover from future disasters. Incorporating indigenous knowledge with national DRR strategies, supported by the government and NGOs, can empower Kutubdia residents to cope better against evolving climate change challenges by safeguarding their livelihood and built environment.

References

Adaan Uzzaman, S. (2023). Tapping Into Bangladesh’s Wind Power Potential - The Confluence. The Confluence. Available at: https://theconfluence.blog/tapping-into-bangladeshs-wind-power-potential/ (Accessed: 13 January 2025).

Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan 2009. (2009). Dhaka: Ministry of Environment and Forest, Government of Bangladesh. Available at: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC163540/ (Accessed: 18 January 2025).

Bangladesh National Social Welfare Council. (2022). Report on Unemployment Status and Health Issues of Salt Bed Workers: A Study at Kutubdia and Moheshkhali Island, Cox’s Bazar. Dhaka. Available at: https://bnswc.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bnswc.portal.gov.bd/page/685acf84_bea9_49ad_a6e1_c28236b6dc47/2022-07-28-10-05-5ee47341d5807281ea82d0a34a4c6009.pdf (Accessed: 13 January 2025).

Barua, P., Rahman, S. H. and Fellow, P. D. (2017). Indigenous Knowledge Practices for Climate Change Adaptation in the Southern Coast of Bangladesh. The IUP Journal of Knowledge Management.

Billah, M. (2022). Why artificial oyster reefs are the answer to our coastal embankments problems | The Business Standard. The Business Standard. Available at: https://www.tbsnews.net/features/panorama/why-artificial-oyster-reefs-are-answer-our-coastal-embankments-problems-478006 (Accessed: 17 January 2025).

Chowdhury, M. S. N. (2021). The unlikely protector against Bangladesh’s rising seas - BBC Future. BBC Future Planet. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20210827-the-unlikely-protector-against-rising-seas-in-bangladesh (Accessed: 14 January 2025).

Eckstein, D., Kunzel, V. and Schafer, L. (2021). The Global Climate Risk Index 2021. Edited by J. Chapman-Rose and J. Longwitz. Bonn: Germanwatch e.V. Available at: www.germanwatch.org.

Enock, C. and Makwara. (2013). ‘Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Modern Weather Forecasting: Exploring the Linkages’. Journal of Agriculture and Sustainability, 2 (2), pp. 98–141. Available at: https://www.infinitypress.info/index.php/jas/article/view/72 (Accessed: 17 January 2025).

Haq, B. and Chattopadhayay-Dutt, D. P. (2007). Battling the Storm: Study on Cyclone Resistant Housing. 2nd edn. Dhaka: German Red Cross. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.10078177.

Hasan, M. M. and Navera, U. K. (2012). Impact of Climate Change Induced Cyclonic Surge on the Coastal Island: Kutubdia and Sandwip, and Proper Adaptive Measures.

Hossain, E. and Islam, N. (2023). ‘New Age | Cyclone Hamoon hits with heavy wind on Bangladesh coast’. New Age, 24 October. Available at: https://www.newagebd.net/article/215816/cyclone-hamoon-hits-with-heavy-wind-on-bangladesh-coast (Accessed: 18 January 2025).

Huq, S. and Reid, H. (2007). ‘A vital approach to the threat climate change poses to the poor: community-based adaptation’. in IIED Briefing. London: International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED),. Available at: www.iied.org.

Ikeda, N., Narama, C. and Gyalson, S. (2016). ‘Knowledge sharing for disaster risk reduction: Insights from a glacier Lake workshop in the Ladakh Region, Indian Himalayas’. Mountain Research and Development. International Mountain Society, 36 (1), pp. 31–40. doi: 10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-15-00035.1.

Islam, M. K., Fahad, M. N. H., Chowdhury, M. A. and Islam, S. L. U. (2023). ‘Shoreline change rate estimation: Impact on salt production in Kutubdia Island using multi-temporal satellite data and geo-statistics’. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment. Elsevier, 30, p. 100957. doi: 10.1016/J.RSASE.2023.100957.

Kamal Uddin, A. M. and Kaudstaal, R. (2003). Declination of the Coastal Zone. Dhaka. Available at: www.iczmpbangladesh.org (Accessed: 16 January 2025).

Kuddus, A. (2024). ‘Kutubdia shirking, people rushing to cities’. ProthomAlo, 12 February. Available at: https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/local-news/p2ai3r1v3m (Accessed: 16 January 2025).

Kulig, J. C., Edge, D. S. and Joyce, B. (2008). ‘Understanding Community Resiliency in Rural Communities through Multimethod Research’. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 3 (3). Available at: https://journals.brandonu.ca/jrcd/article/view/161 (Accessed: 13 January 2025).

Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief. (2020). ‘Action for Disaster Risk Management towards Resilient Nation’. National Plan for Disaster Management (2021-2025). Dhaka: Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Available at: https://modmr.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/modmr.portal.gov.bd/page/a7c2b9e1_6c9d_4ecf_bb53_ec74653e6d05/NPDM2021-25%20DraftVer5_23032020.pdf.

NASA, S. L. C. Team. (2021). IPCC 6th Assessment Report Sea Level Projections. IPCC AR6 Sea Level Projection Tool. NASA Sea Level Change Portal. Available at: https://sealevel.nasa.gov/ipcc-ar6-sea-level-projection-tool (Accessed: 14 January 2025).

Partha, P. (2024). ‘Rethinking Disaster Response: We ignore indigenous knowledge at our peril’. The Daily Star, 1 October. Available at: https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/views/news/rethinking-disaster-response-we-ignore-indigenous-knowledge-our-peril-3716491 (Accessed: 17 January 2025).

Parvin, A. and Johnson, C. (2012). Learning from the indigenous knowledge: towards disaster-resilient coastal settlements in Bangladesh.

Parvin, G. A., Takahashi, F. and Shaw, R. (2008). ‘Coastal hazards and community-coping methods in Bangladesh’. Journal of Coastal Conservation. Kluwer Academic Publishers, 12 (4), pp. 181–193. doi: 10.1007/s11852-009-0044-0.

Shahriar, S. (2015). Kutubdia: the vanishing island. BBC Media Action. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/mediaaction/stories/kutubdia-the-vanishing-island (Accessed: 13 January 2025).

Tanim, S. H. and Roy, D. C. (2013). ‘Climate-Induced Vulnerability and Migration of the People from Islands of Bangladesh: A Case Study on Coastal Erosion of Kutubdia Island’. in Planned Decentralization: Aspired Development. World Town Planning Day 2013.

MetLink. (2020). ‘The Deadliest Storms on Record: The Bangladesh Cyclones of 1970 and 1991’. in Introduction to Tropical Meteorology. 2nd edn. Royal Meteorological Society. Available at: https://www.meted.ucar.edu/tropical/textbook_2nd_edition/navmenu.php?tab=9&page=8.2.0 (Accessed: 18 January 2025).

The Financial Express. (2018). ‘Tidal surge maroons 10,000 villagers in Kutubdia’, 19 July. Available at: https://today.thefinancialexpress.com.bd/country/tidal-surge-maroons-10000-villagers-in-kutubdia-1531928610 (Accessed: 10 January 2025).

The Financial Express. (2019). ‘Tidal surge inundates 16 villages in Kutubdia’, 9 July. Available at: https://today.thefinancialexpress.com.bd/country/tidal-surge-inundates-16-villages-in-kutubdia-1562598382 (Accessed: 13 January 2025).

Ullah, M. D. R. (2024). ‘NGOs’ Role in Sustaining Indigenous Knowledge in Rural Bangladesh: Agriculture, Healthcare, and Disaster Management’. South Asian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. ACS Publisher, 5 (1), pp. 79–102. doi: 10.48165/sajssh.2024.5106.

Yusuf, Sk. S. and Mustafi, N. N. (2018). ‘Design and Simulation of an Optimal Mini-Grid Solar-Diesel Hybrid Power Generation System in a Remote Bangladesh’. International Journal of Smart grid. International Journal of Renewable Energy Research. doi: 10.20508/IJSMARTGRID.V2I1.7.G8.